Blog

How to Comply With the DoD’s Newer and Stricter Software Requirements

We break down H.R. 7900, a well-intentioned but perhaps unrealistic bill that requires companies working with the DoD to provide a software bill of materials (SBOM) and patch all known vulnerabilities.

On August 17, the US House of Representatives passed H.R. 7900 – National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2023, and section 6722 could have serious impacts on the information security industry and beyond.

Section 6722. DHS Software Supply Chain Risk Management

According to the bill, New and existing “covered contracts” with the Department of Defense (DoD) or the Department of Energy (DoE) are now required to provide a Software Bill of Materials (SBOM) in addition to ensuring that all listed software components do not contain any known vulnerabilities.

Under section 6722 (i), a “covered contract” is defined as any contract relating to the procurement of “covered information and communications technology or services for the Department of Homeland Security.”

These types of products and services are considered to be covered technologies or services:

- Information technology

- Information system(s)

- Telecommunications equipment

- Telecommunications service(s)

- Software

Section 6722 (e) – Certification and Notifications

According to subsections (e) (1), a contracting authority within the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) must provide a certification stating that all SBOM components are free from any vulnerability or defect found in NVD, or any database maintained by the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA)—including the Known Exploited Vulnerabilities (KEV) Catalog.

Section 836’s current language suggests that without both a SBOM and certification, covered contracts will not pass procurement. As such, comprehensive vulnerability intelligence (VI) is critical for those beholden to H.R. 7900 since vulnerability management processes are directly dependent on VI.

The problems with H.R. 7900

Organizations looking to comply with H.R. 7900 will likely struggle with two main pain points—H.R. 7900’s poor language and the quality of publicly available data.

Poor language

“[…] A certification that each item listed on the submitted bill of materials is free from all known vulnerabilities or defects…”

H.R. 7900, Section 6722 (e)(1)

Despite good intentions, legislation requiring organizations to address every vulnerability is problematic for many reasons. First and foremost, it favors a top-down or patch-all mindset, which has produced little improvements to security over the past decade. Trying to fix every vulnerability requires significant resources, and there are simply too many to address in a timely manner.

VulnDB® Enables Continuous Product Security for Dräger

With VulnDB, Dräger has comprehensive vulnerability intelligence that includes both Open Source Software (OSS) and commercial software, enabling continuous security during development and post-release.

Secondly, H.R. 7900’s blanket statement of “all known vulnerabilities or defects” does not allow for the contextualization of any vulnerability and how it relates to overall risk. Not all vulnerabilities are the same, and metrics such as CVSSv2 or CVSSv3 are used to reflect that. However, H.R. 7900’s language does not acknowledge any kind of caveat, other than that vulnerabilities contained in NVD or CISA’s databases cannot be present.

This is a problem because Section 6722 (e) (1) ignores factors such as severity, attack location, and exploitability. Depending on those details, even if a vulnerability is present it could have little-to-no impact on the integrity of the software. For example, if there is no path to exploitable code, threat actors have no means to actually exploit it. While organizations could just remove all instances of vulnerable code in that situation, it may not be so simple—doing so could potentially create new unforeseen bugs and problems.

Additionally, although some vulnerabilities are exploitable, their attack locations may make exploitation highly unlikely. Vulnerabilities with a “physical” attack location—meaning that malicious actors must be physically present to exploit—are unlikely to occur given the physical security capabilities of the government, in addition to the majority of nation state hackers residing in foreign nations. The same can be said for vulnerabilities that can only be exploited through Bluetooth connections. However, H.R. 7900 does not allow for these distinctions.

Built around CVE / NVD data

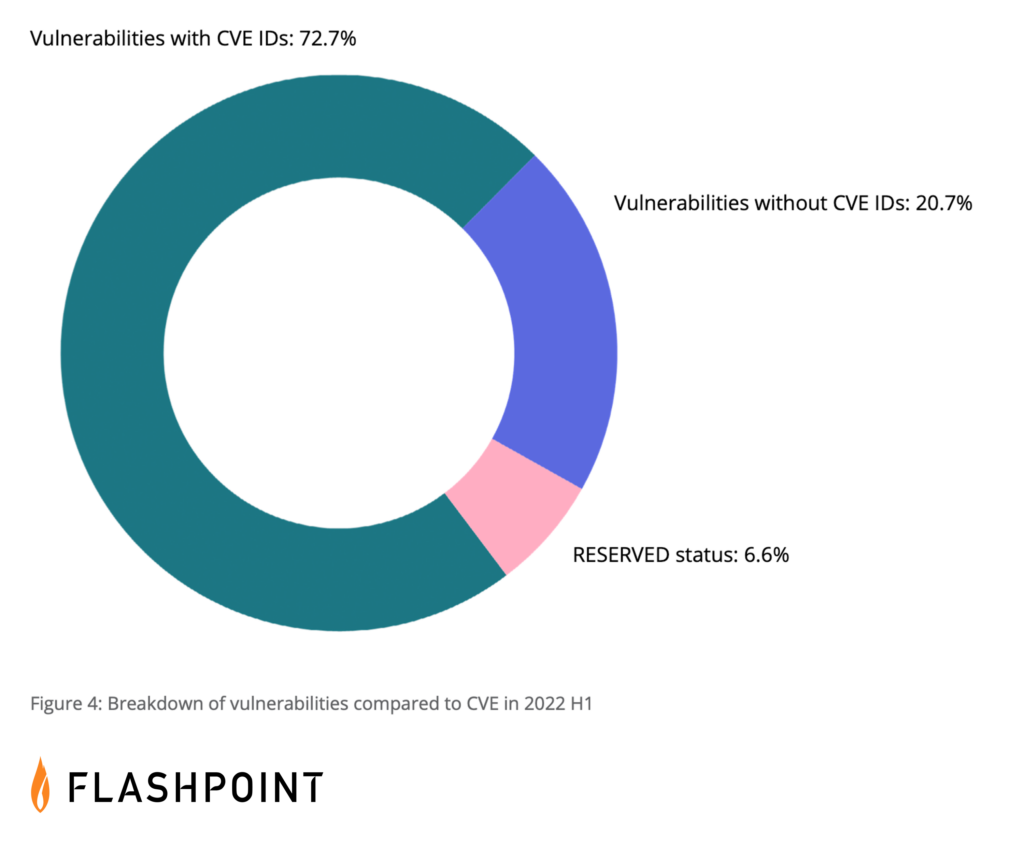

The primary concern however is that Section 6722 is based on NIST’s National Vulnerability Database. NVD’s entries are dependent on a CVE ID, and therefore, if a CVE ID has not been assigned, it will not exist in NVD. At time of publication, CVE / NVD have failed to report over 94,000 vulnerabilities in total, and in the first six months of this year, could not detail 27.3 percent of all disclosed vulnerabilities.

As such, even if organizations were to provide a bill of materials that did not contain any CVEs, it does not guarantee that the technology or service is secure, even to public vulnerabilities. Not only due to CVE’s overall delta in coverage, but also because of what is included in that difference. CVE significantly lacks visibility into vulnerabilities affecting third party libraries and open source software (OSS)—which is what ultimately will comprise the majority of SBOMs.

How H.R. 7900 could affect you

In the end, the inherent problems found in H.R. 7900 and CVE / NVD will result in increased workloads, stress, and likely less software sold.

While organizations can provide remediation plans and explain issues such as “resolved” CVE issues (vulnerabilities affecting unpatched, older versions), contracting officers might not fully grasp the multitude of vulnerability caveats previously explained. Therefore, if a CVE ID exists, it will likely need to be addressed for the contract to be approved. Unfortunately, CVE / NVD often misses important vulnerability metadata such as solution information, so security teams will often have to conduct their own research to find those details.

RESERVED status vulnerabilities will make research more difficult

CVEs that are in RESERVED status will also make researching more difficult, as they are vulnerabilities that are given IDs but contain no details. That includes the base vulnerability details that come from MITRE, and the additional metadata generated by NVD. Even when an ID is open, sometimes solution information is available, but it cannot be found in CVE / NVD—meaning that without comprehensive VI, security teams will have to scour the web for any information. Some RESERVED status vulnerabilities occasionally end up on CISA’s KEV catalog due to their high exploitability. Collecting details for these kinds of RESERVED status issues means security teams have to burn extra cycles doing the research, as they tend to be zero-days or discovered-in-the-wild vulnerabilities.

“Not A Vulnerability” entries could become a blocker

“Not A Vulnerability” (NAV) entries could also be a major headache for organizations. Last year, 307 CVE IDs were deemed not to be a vulnerability and despite them not being actual issues, they still possess CVE IDs. These often occur due to validation checks not being performed, or in situations where an issue was deemed to be a non-issue after its initial disclosure. Unfortunately, NAV entries still occur and likely will continue due to CVE’s current reporting structure and lacking QA process. If a NAV exists for a software or a listed OSS component, current language suggests that this will become a blocker, and organizations may not have much luck communicating this to contracting officers—especially if CVE does not update their descriptions.

H.R. 7900’s potential impact on the security community

With all of this into consideration, H.R. 7900 could have lasting impacts on the vulnerability disclosure landscape and the security industry as a whole. The language in this bill shows that lawmakers consider vulnerability totals to be an indicator of security and this is not true. Vulnerability totals should not be used for the basis of product comparisons or security assessments. The following can impact a vendor or product’s vulnerability count:

- Overall market share, or product-market share

- Routine (or lack of) schedule of disclosures

- Attention from vulnerability researchers

- Vendor response time / patch time

- And more

Who is at a disadvantage from H.R. 7900?

Enterprises and well-known vendors could be at a disadvantage from H.R. 7900. Larger organizations tend to have more vulnerabilities affecting their products—but they also tend to be faster at patching them. However, the overall use and attention that these kinds of products receive results in a constant stream of new vulnerabilities being discovered. This could put enterprises in a constant state of gridlock where they are constantly validating issues, triaging them, and creating new notifications to inform the DHS how they plan on addressing them.

This could lead the DHS to purchase more proprietary software, or work with lesser-known vendors. While beneficial for those vendors, it does not guarantee that those products are more secure. It is likely that lesser-known products will contain less CVE identified vulnerabilities, but that often stems from fewer vulnerability researchers investigating their products. And while CVE / NVD, or CISA may think that there are no issues, lesser-known products can contain critical vulnerabilities that fail to get reported to CVE.

H.R. 7900’s potential influence on new vulnerabilities

If H.R. 7900 is strictly enforced, this bill could potentially incentivize vendors to not publicly disclose new vulnerabilities. We have already seen some organizations in the past employ bug bounty programs that force vulnerability researchers sign NDAs, preventing them from publicly disclosing issues. Could the industry see a possible future increase in behavior? Could we also see crowdsourced vulnerability databases and other community projects face future pressure?

Identify and remediate vulnerabilities with Flashpoint

H.R. 7900 has the potential to be problematic and its enforcement is unclear. However, for organizations being forced to, or are looking to be compliant, they will need comprehensive and detailed vulnerability intelligence. Flashpoint’s VulnDB® contains over 297,000 vulnerabilities affecting computer hardware, software, third party libraries, and open source components. Sign up for a free trial to identify all known vulnerabilities affecting your product and listed components—and remediate or mitigate them today.

Do you have certain products, third party libraries or OSS components that you need researched? Contact us to add specific coverage to your vulnerability intelligence needs.