Blog

Mobile Apps and Chat Services Key to Flourishing Chinese Cybercrime

Cybercriminals worldwide continue to migrate their illicit operations away from forum-oriented marketplaces to more secure and anonymous mobile chat services. Nowhere is this more apparent than within Chinese cybercrime communities, which have long sought to offer digital refuge shielding against mass government surveillance and draconian internet constraints, such as “The Great Firewall.”

Mobile Chat: De Facto Infrastructure for Chinese Cybercrime Operators

Cybercriminals worldwide continue to migrate their illicit operations away from forum-oriented marketplaces to more secure and anonymous mobile chat services. Nowhere is this more apparent than within Chinese cybercrime communities, which have long sought to offer digital refuge shielding against mass government surveillance and draconian internet constraints, such as “The Great Firewall.”

Chinese members, both within and outside of the physical country borders, increasingly flock to these mobile cybercriminal exchanges to purchase a wide assortment of government-banned products along with the more familiar illicit cybercriminal listings, including sensitive data, malware, ransomware, phishing exploit kits, distributed denial of service (DDoS)-as-a-Service, and more.

Mobile App “QQ” is a One-Stop Chinese Cybercrime Shop

Similar to other mobile apps like Telegram or WhatsApp but far bigger in scale and scope (and the 5th most-visited website worldwide), the Chinese app Tencent QQ primarily serves law-abiding users with social chat capabilities and a wide range of connected eCommerce and internet services. QQ is also similar to these other apps in that cybercriminals and other threat actors leverage the online platform to conduct their illicit business and varied cyber operations.

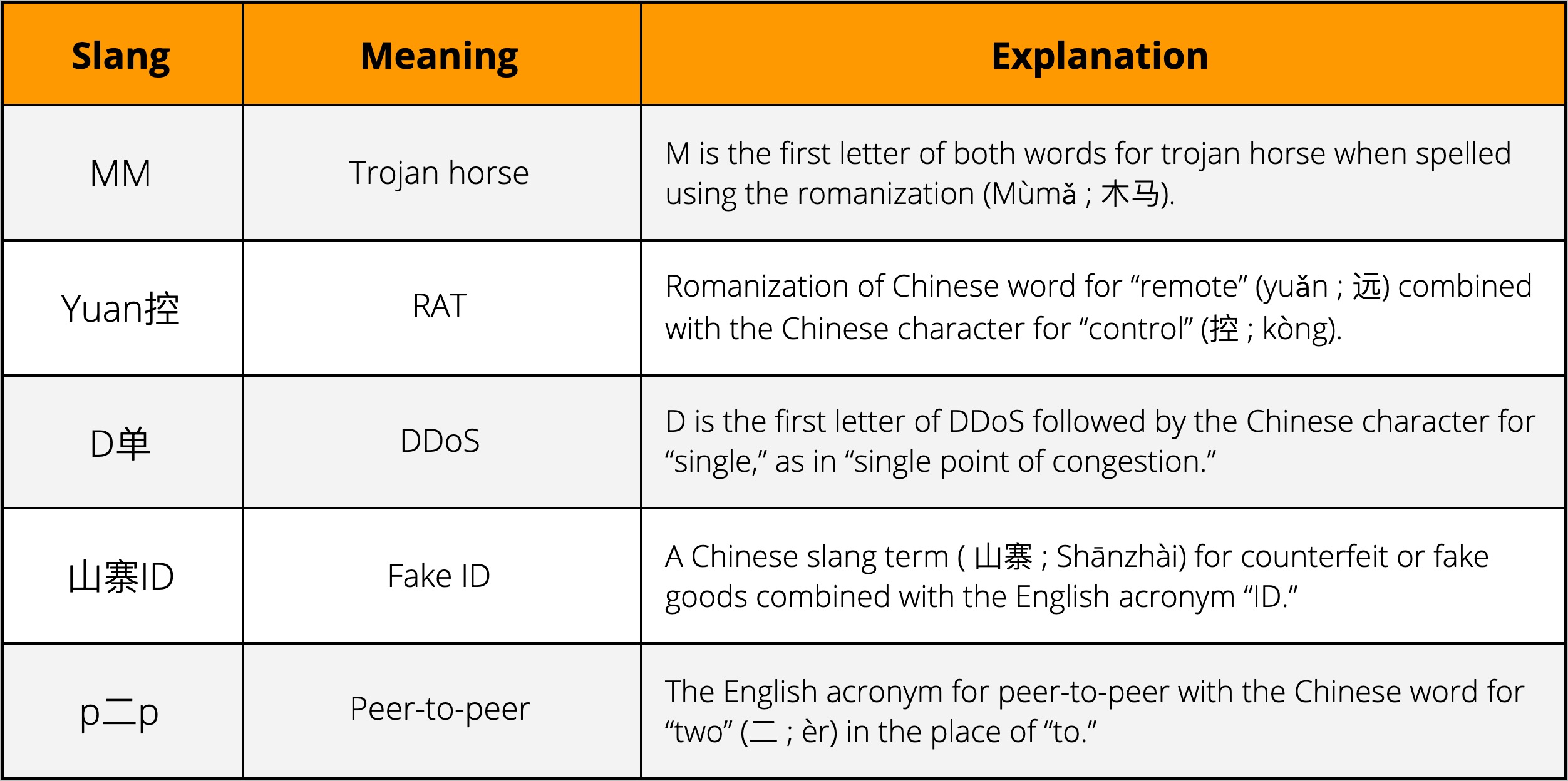

Chinese Cybercrime Slang Mixes in Chinese and English Characters, Memes, and Emoticons

On Chinese cybercrime forums, actors communicate using a broad base of mixed languages and character sets. The Simplified Chinese character set acts as the primary language foundation and are routinely appended by a medley of specialized typographic modifiers in the forms of other traditional Chinese and English characters, local Chinese dialects, unique acronyms, emoticons, memes, and more. This elaborate, and often convoluted cybercriminal language, further obfuscates cybercriminal activity and often makes threat detection and disruption more challenging for the typical.

Figure 1: Common Chinese Cybercrime Slang Phrases

Chinese Cybercriminals Offer Familiar List of Illicit Wares

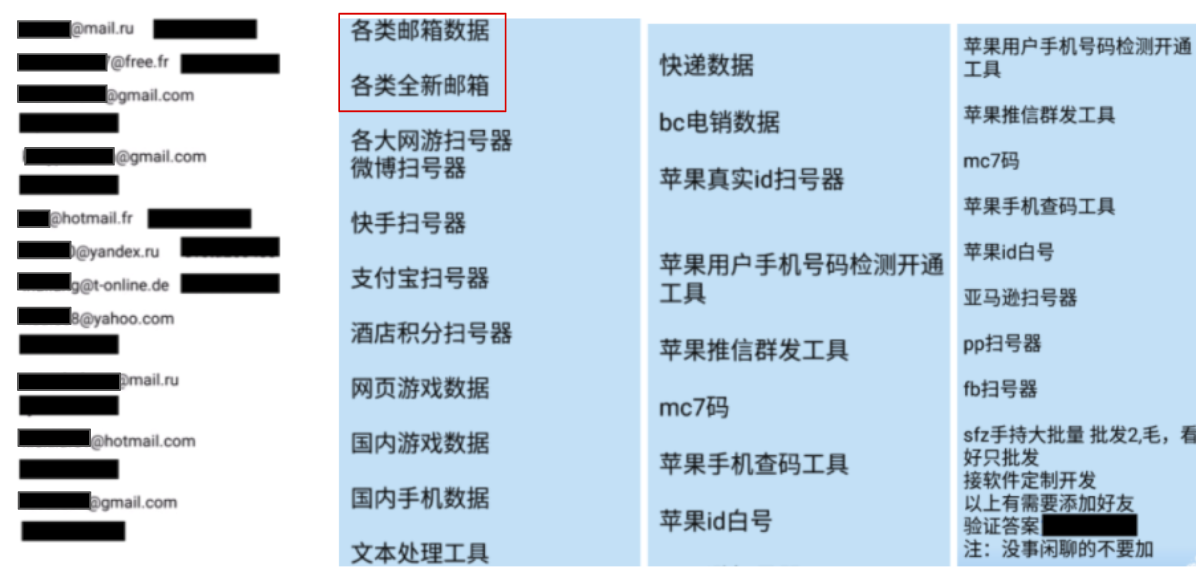

While using innocuous group names and slang obscures their activity to a certain degree, once these conversations are ultimately decoded, we find a robust Chinese cybercriminal community. There are active exchanges discussing a familiar list of illicit cybercriminal goods and services with similar pricing structures, including offerings for fake or compromised account sales, database sales, synthetic identity fraud, carding, and other malicious activity.

Flashpoint regularly observes cybercriminal posts that advertise databases and tools for sale to monetize both freshly harvested and previously found data. In the example below, Flashpoint obtained samples from a database of “various kinds of email data,” pictured in the red box and shown at left (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Sample of Chinese Database and Exploit Offering

Phishing, Ransomware, and DDoS Also Top Chinese Listings

Given the abundance and relative efficacy of phishing, ransomware, and DDoS attacks, it’s no surprise that these offerings top Chinese cybercriminal listings. For phishing in particular, TTPs to surface source code for phishing sites are of particularly high interest for community members. As ransomware continues to prove lucrative, Chinese cybercriminals increasingly turn to the attack method as well. In the ransomware-themed Chinese group below (see Figure 3), Flashpoint displays the group’s file sharing container and the ransomware file names and labels. While group discussions do not indicate any specific plans of organized ransomware attacks, it’s clear that malware and related exploit files are routinely distributed.

DDoS is another large area of Chinese cybercriminal discussion, especially automated and managed services to execute DDoS campaigns with minimal uplift from the cybercriminal buyer. In these scenarios, DDoS attacks support threat actors’ objectives by acting either as a stress testing instrument or as one of the leveraged weapons in the attack itself (see Figure 4). In the example below, a meme posted to a QQ group advertises DDoS-for-hire services.

Figure 3: File Repository of Ransomware-Themed Chinese Cybercriminal Group

Figure 4: DDoS-as-a-Service Meme Advertisement

Chinese Cybercriminals More Open to Collaboration and TTP Sharing

Chinese group members appear to more regularly and openly share tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) and related services to target specific phases of the attack kill chain—especially in cases where the objective is to circumvent onerous Chinese government-enforced internet restrictions, such as proxy recommendations to bypass the Great Firewall. To further facilitate these efforts, chat members stand up shared file systems that enable easy coordination and distribution of necessary information, malware, and toolsets. However, financial gain remains Chinese cybercriminals’ primary motive.

Leverage Flashpoint’s APAC Intelligence and Native-Language SMEs

Sign up for a demo today! Learn how Flashpoint Intelligence rapidly dissects threat actor linguistic tricks and keeps tabs on illicit cybercriminal activity throughout China and the rest of the Asia-Pacific region. In addition, Flashpoint automated collection and analytics are further buttressed by our experienced native-language analysts and curated in-region intelligence tradecraft to identify new and emerging APAC threats.