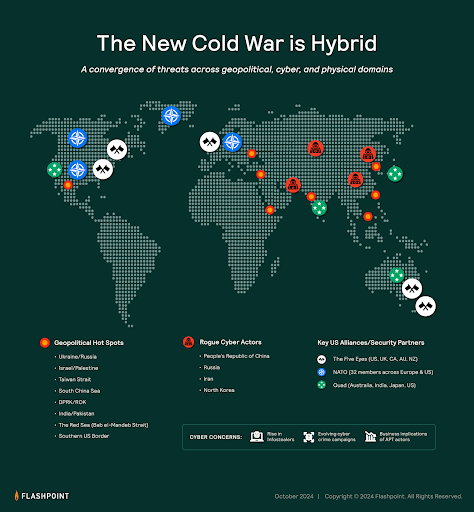

On October 7, following Hamas’s unexpected attack on Israel, a spectrum of cyber actors turned to social media to both condemn and endorse the attacks. Shortly thereafter, hacktivists joined the fray, engaging in defacements and Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) attacks on various Israeli and Palestinian websites. While the context of these attacks are unique to the Israel-Hamas War, they do generally echo a playbook we’ve previously observed in other modern military conflicts. These patterns deserve a closer look.

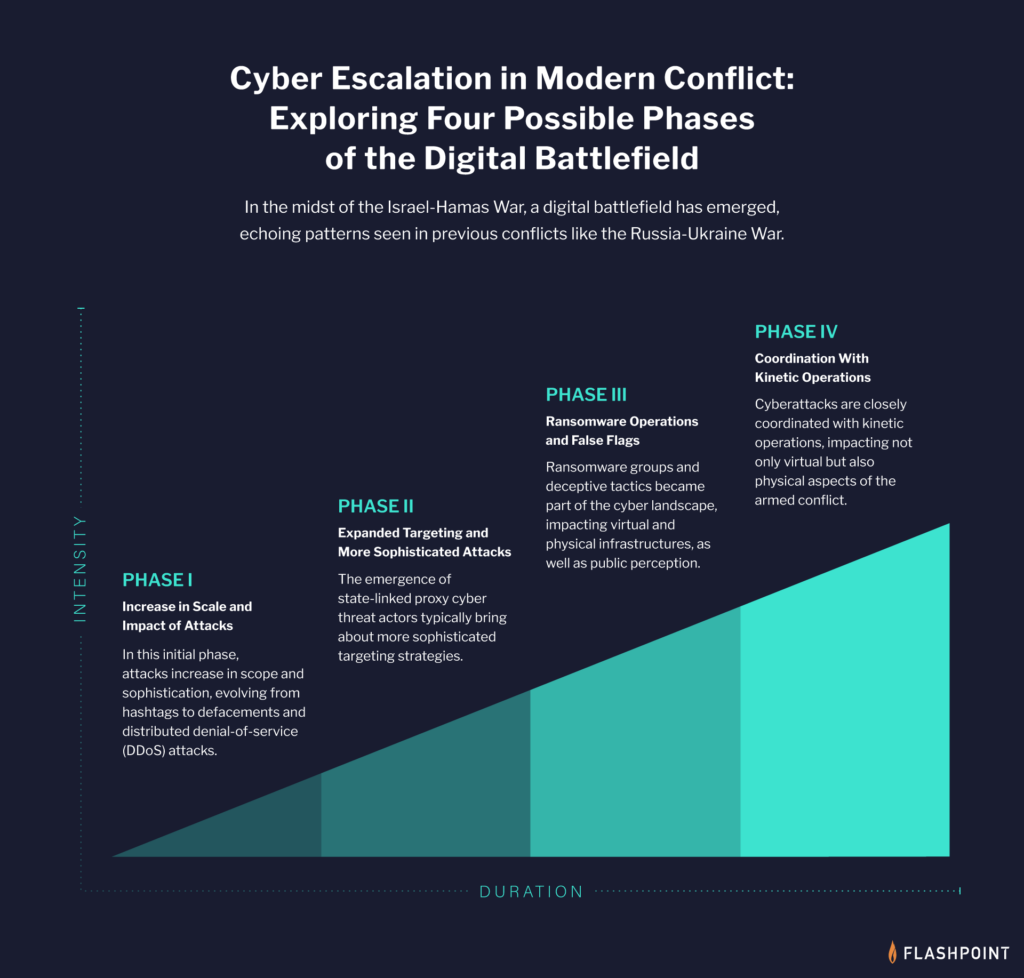

In the midst of the Israel-Hamas War, a digital battlefield has emerged, echoing patterns seen in previous conflicts like the Russia-Ukraine War. This exploration delves into the intricacies of four possible waves of cyberattacks and cyberterrorism. These phases not only illustrate the evolving nature of cyber threats but also blur the lines between virtual and physical battlegrounds. Though the war is still unfolding at a rapid pace, we anticipate that the role of cyber warfare may play out in a similar nature to the Russia-Ukraine War, and demonstrate the following four phases.

We will unravel the following phases:

- Phase 1: Increase in Scale and Impact of Attacks

In this initial phase, attacks increase in scope, evolving from hashtags to defacements and distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks. - Phase 2: Expanded Targeting and More Sophisticated Attacks

The emergence of state-linked proxy cyber threat actors typically bring about more sophisticated targeting strategies, including cyberterrorism. - Phase 3: Ransomware Operations and False Flags

Ransomware groups and deceptive tactics become part of the cyber landscape, impacting virtual and physical infrastructures, as well as public perception. - Phase 4: Coordination with Kinetic Operations

Cyberattacks are closely coordinated with kinetic operations, impacting not only virtual but also physical aspects of the armed conflict.

The Four Phases of Cyber Warfare

While the boundaries between each of the following phases can blur, noting further that they may not occur in a specific order and may overlap, these phases can help characterize the typical progression of cyber warfare between state and non-state groups.

Phase 1: Increase in Scale and Impact of Cyberattacks

On October 7, following Hamas’s unexpected attack on Israel, a range of cyber actors took to social media, both condemning and praising Hamas’s actions. Shortly thereafter, hacktivists joined through defacements and denial of service (DDoS) attacks on various domains of Israeli and Palestinian websites.

Initial attacks began with hashtags expressing support for both sides. This phase escalated to include defacements of Israeli and Palestinian government top-level domains (TLDs) and extended to businesses operating in these regions. Hacktivists shared open-source DDoS tools. Targeting expanded to include diplomatic partners of both sides, mirroring previous attacks against Western entities during the Russia-Ukraine War.

Phase 2: Expanded Targeting, Sophistication

Numerous hacktivist groups pledging allegiance to both pro-Israel and pro-Hamas causes are known to communicate through online channels, including Telegram and X (formerly Twitter). The extent to which these groups are actively coordinating cyberattacks or cyberterrorism in light of the ongoing conflict is not fully transparent. However, notable hacktivist collectives, such as Anonymous Sudan and Killnet, have publicly declared their participation in cyber offensives against targets within Israeli and Palestinian territories.

Advanced Persistent Threat Groups (APTs) are also playing a significant role in the Russia-Ukraine conflict. However, state-supported adversaries, acting autonomously but with government approval, also emerged. The extent of coordination between these groups and state intelligence agencies remains unclear. These proxy groups provided plausible deniability to their host governments. Examples include Killnet and Anonymous Sudan, which had previously targeted Western entities during the Russia-Ukraine War.

Phase 3: False Flags and Ransomware Operations

In addition to proxy groups and state-supported adversaries, ransomware groups entered the conflict. Killnet claimed to align with members of the ransomware group REvil, and other adversaries like “T.Y.G Team – 1915 Team” claimed to use ransomware attacks against Israel, possibly leveraging their own brand of ransomware like “Gaza Digital Storm.” This also attracted the affiliates and initial access brokers with apparent access to Israeli and Palestinian infrastructure.

Operational Technology (OT) and Critical Infrastructure within Israel are already being touted as targets. Critical infrastructure sectors such as Telecommunications/Command and Control, Petroleum, Oil, Lubricants, and Electricity are often targeted in major conventional military conflicts. Therefore, if Israel is conducting any cyber warfare or military operations within Gaza, it should be expected that parts of the critical infrastructure would be targeted in the early stages. This targeting, actual or perceived, can affect the progression of the war.

For example, “Cyber Av3ngers” claimed to have successfully hacked the Dorad Power Plant. This attack had previously been linked to a possibly Iranian state-sponsored group dubbed “Moses Staff,” which itself had also been linked to Iranian group “Abraham’s Ax.”

This incident, which was subsequently debunked on social media platforms, might have been prematurely regarded as a forewarning. However, it also underscores that such groups pursue objectives beyond mere disruption; they aim to garner attention, cultivate notoriety, or stir up fear, uncertainty, and doubt (FUD).

“SiegedSec,” another hacktivist group that has been active during the Russia-Ukraine War, has also claimed denial of service attacks against Israeli infrastructure with “Anonymous Sudan.” In Israel, Anonymous Sudan also claimed to have conducted distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks on the apps “tzevaadom” and “Red Alert.” Predatory Sparrow (AKA Gonjeshke Darande), an English- and Persian-speaking hacktivist group, has been responsible for carrying out some of the most sophisticated, disruptive, and destructive cyberattacks targeting Iran in at least ten years, with suspicions of being a state in opposition to Iran. The group re-emerged on Telegram shortly after the start of the Israel-Hamas War, announcing their return.

Phase 4: Coordination with Kinetic Operations

In the initial phase of the invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, major wiper malware attacks against Ukrainian government systems coincided closely with the timing of Russian airstrikes and troop movements. It is likely that as the Israel-Hamas war continues, there may similarly be coordination with kinetic operations, either preceding the attacks or occurring simultaneously.

Coordination between cyber and kinetic operations is likely to increase as the Israel-Hamas War continues. There may be attempts to disrupt internet access, similar to the early phases of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Continued attacks on infrastructure, connectivity, and potential targeting of Operational Technology (OT) are anticipated.

Best Cyber Practices for Businesses in Times of Modern Warfare

Amid the challenges that arise in times of modern conflict, businesses must prioritize the security of their operations, assets, and employees. The ongoing Israel-Hamas and Russia-Ukraine wars, along with the evolving nature of cyber threats and their interrelatedness with the physical world, offer valuable insights for building resilience. Embracing these practices and remaining vigilant against cyber threats can better ensure safety, resilience, and the ability to thrive even during conflicts. Get in touch with us today.

“Flashpoint’s advanced CTI solutions address customer pain points and proactively mitigate risks to safeguard their people, places and assets. This strategy empowers organizations to confidently combat cyberattacks.”

Frost and SUllivan